Amazon Comprehend Medical and AI in Healthcare

Ben Guzman*, Isabel Metzger, Yin Aphinyanaphongs, Himanshu Grover*

The field of medicine is undergoing a massive transformation with widespread adoption and meaningful use of health information technology, promoted by the HITECH (Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health) Act of 2009. With clinical practice now becoming increasingly data-driven, new tools powered by machine learning and artificial intelligence are being mobilized to solve tough problems.

A large proportion of patient healthcare data is recorded in the form of free-text narratives, such as admission and progress notes, consult notes, and discharge summaries. A few numbers (from United States) will put the scope into perspective: 35.1 million hospital discharges (2010), 51.4 million procedures performed (2010) and 125.7 million outpatient department visits (2011). Each of these encounters produced at least one medical note. This gold-mine of information largely remains locked away due to the complex nature and composition of medical notes. The promise of an intelligent, data-driven health system relies on the ability to extract knowledge from this digital footprint, to drive reporting, compliance, and improvements in the delivery of care.

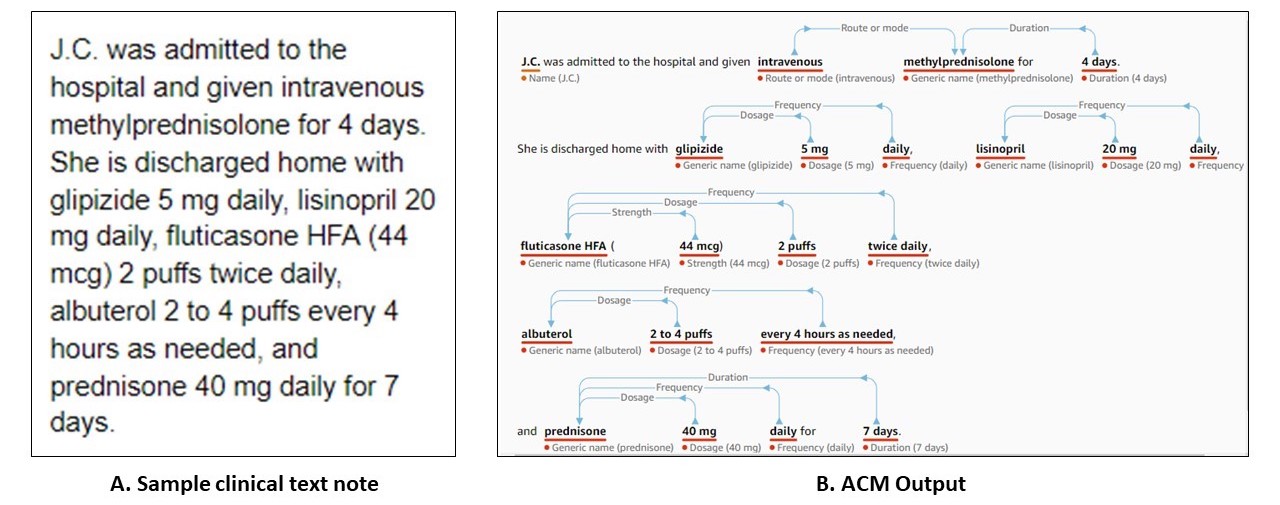

Recently, several commercial companies have started providing pay-to-use APIs that ingest medical notes and extract relevant information in a structured format that is more amenable to further analysis and use in downstream applications. A notable example is Amazon Web Services’ (AWS) Comprehend Medical (ACM). ACM’s API endpoint processes unstructured clinical notes and outputs structured entities and their relationships derived from concepts such as medical conditions, lab tests, medications, treatments, and procedures, in addition to protected health information (PHI) [1]. From what we have gathered from several recently published papers, the machinery behind ACM is driven by state-of-the-art deep learning algorithms [2-5]. A sample output from ACM web console, as shown in Figure 1, demonstrates the nature of information extracted.

Figure 1: (A) Sample clinical text note as adapted from Koda Kimble and Young’s Applied Therapeutics - The Clinical Use of Drugs: Case 102-5 [6] and (B) ACM’s web console output, with extracted medical entities and their relationships.

Figure 1: (A) Sample clinical text note as adapted from Koda Kimble and Young’s Applied Therapeutics - The Clinical Use of Drugs: Case 102-5 [6] and (B) ACM’s web console output, with extracted medical entities and their relationships.

ACM presents a compelling product in the form of a single, easy-to-use API to extract information, and thus clinical value from medical notes. However, uptake and trust in any new data product relies on independent validation across datasets and/or tools to establish and confirm expected quality of results. In that spirit, we validated ACM’s initial version that was released on November 27, 2018. Specifically, we focused on the medication extraction sub-task, which seeks to draw out medication entities and relationships from medical notes. This is a crucial task as medications play a vital role in patient care. In this context, ACM can surface the following fields of information: a) generic and brand name, b) dosage, c) frequency, d) route/mode, e) duration, f) strength, and g) form, and h) rate.

We conducted our evaluation on the publicly available benchmark dataset from the 2009 Informatics for Integrating Biology & the Bedside (i2b2) Medication Extraction Challenge. This dataset was compiled from discharge summaries from Partner’s Healthcare in Boston, MA. Using such a benchmark is ideal because it allows consistent comparison across systems built for the same task. In this dataset, 696 notes were designated as training set for building the algorithms and 251 notes were reserved for unbiased testing. Test set notes were manually annotated for targets of interest, which included only medication name, dosage, frequency, route/mode, and reason [8]; these comprise the gold-standard (true) labels for evaluation. We measured the performance of ACM on the test set, using the competition’s three evaluation metrics:

- Precision, which captures the proportion of gold-standard labels among all labels assigned by the system.

- Recall, which captures the proportion of all gold standard labels in the test set that are recovered by the system.

- F-score is the harmonic mean of precision and recall, which can be used as a single composite metric concealing the tradeoff between precision and recall.

We compared ACM’s performance with: a) Patrick et. al [9], which uses a combination of machine learning and rule-based methods; b) Doan et. al [10], which was a purely rule-based algorithm; and c) Tao et. al [11], which is a more recent machine learning algorithm developed using the i2b2 dataset. The first two were the top two performers in the medication extraction challenge, respectively. As in the original competition, F-score is the main evaluation metric used to compare the different systems.

Table 1 summarizes the results from our preliminary investigation. In the context of the i2b2 test dataset, and on this specific task, ACM appears to achieve the lowest F-score among all systems compared.

Table 1. System performance on the i2b2 test set.

| System | Recall | Precision | F-Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patrick et. al | 0.896 | 0.820 | 0.857 |

| Doan et. al | 0.840 | 0.803 | 0.821 |

| Tao et. al | 0.848 | 0.879 | 0.864 |

| ACM-without-reason | 0.801 | 0.737 | 0.768 |

| ACM-perfect-reason | 0.814 | 0.753 | 0.782 |

| ACM-competitive-reason | 0.797 | 0.713 | 0.752 |

One limitation that we encountered was due to ACM’s inability to detect the “reason” attribute for medication intake. For example, consider this short note: “patient took motrin 200 mg tablet for pain and fever.” In this case, the dataset would contain two entries for reason extraction: a) motrin 200 mg tablet for pain, and b) motrin 200 mg tablet for fever. However, since ACM does not recognize reasons, it extracts only one output - “motrin 200 mg tablet” - from the narrative.

Omission of these entries does affect the performance numbers and makes the comparison with other systems only approximate since those systems did take “reason” extraction into account. For the sake of simplicity, in our initial analysis we excluded all the “reason” entries while computing ACM performance (ACM-without-reason in Table 1). There are a total of 1,342 such instances in the i2b2 test dataset, accounting for approximately 6% of all extraction targets.

To circumnavigate this subtlety, we also re-computed ACM performance for: a) perfect-case scenario (ACM-perfect-reason in Table 1), assuming ACM correctly extracts all “reason” entries, and b) competitive-case scenario (ACM-competitive-reason in Table 1), assuming ACM correctly extracts as many reason entries as the best performer on the reason dimension on this dataset [9].

Interestingly, even the perfect-case adjustment bumps up ACM’s performance only to a F-score of 0.782, which is still lower than all other systems compared. In contrast, Doan et. al’s algorithm and open source system achieves almost six percentage points higher than ACM.

From our observations, one of the common sources of error pertains to misclassification of certain medications by ACM as treatment names. Some examples that surfaced include oxygen, packed red blood cells, chemotherapy, ace inhibitor, diuretics, beta-blockers, and angiotensin II receptor blockers. While one could argue that this is a matter of interpretation, these nuances could have implications for specific use-cases, particularly when they serve as inputs to automated downstream applications.

Another curious behavior that we observed was ACM’s sensitivity to white space. For example, if the complete medication name “polysaccharide iron complex” happens to have a new line inserted after polysaccharide, the extracted entity by ACM only included “iron complex”. Given the fact that clinical notes are plagued with numerous syntactic and grammatical issues, this behavior can significantly impact performance and yield unstable results.

Notwithstanding these shortcomings, that are not unusual in a complex data product, the benefits that ACM provides are real. First and foremost, it provides a clean API that can easily scale to handle large workloads while ensuring data security and privacy. While our analysis focused solely on the medication extraction subtask, several other important informational elements can be extracted with the same API call. The underlying deep learning models and technology that power ACM have already been implemented and are likely to be updated routinely as end-user requirements evolve. Multiple modes of access—web console and programmatic access via Python or Java—cater to a wide audience with varying levels of skill and facility for technology. All this complexity is hidden from the end-users and requires only modest computing skills for effective use.

In addition, there is no upfront fee or commitment that could lock users into a singular solution, which means users only pay for what they use. This diminishes the need to invest in in-house experts for building advanced algorithms and/or managing large-scale infrastructure to support such algorithms, which is outside the mission of most hospitals and care practices, especially smaller ones.

For most users, these substantial benefits will have to be carefully weighed against the cost factor which can certainly ramp up quickly for blanket use. As of March 2019, cost per unit was fixed at $0.01, where one unit = 100 UTF-8 characters. In our evaluation using the 251 test set notes, which have an average length of 6,643 characters, we incurred approximately $166 for a single analysis run. Scaled use to all medical notes generated by a hospital will likely be cost-prohibitive and highly dependent on the use case, especially for large healthcare systems that may generate several thousands of clinical notes each day. That said, the pay-per-use model may allow institutions to carve out select-use cases that work for them.

Altogether, ACM presents a promising approach with its built-in simplicity and usability. The combination of all the above factors can empower end-users to innovate and drive usage. In terms of performance, at least for now and for the medication extraction subtask, better open source alternatives do exist. But they come with their own trade-offs regarding human and computing resources required to operate them, and other similar models in this space, at scale. It will definitely be interesting to see how ACM as a product and its adoption into clinical workflows evolve over time.

Our team is conducting further analyses on ACM's core capabilities and how it may fit into our operational requirements. These additional details and comparisons will be published in the near future.

For correspondence about this work, you may contact Ben Guzman at bvg228@nyu.edu or Himanshu Grover at himanshu.grover@nyulangone.org.

References:

- Amazon Web Services. Accessed May 15, 2019 from https://aws.amazon.com/comprehend/medical/.

- Jin M, Bahadori MT, Colak A, Bhatia P, Celikkaya B, Bhakta R, Senthivel S, Khalilia M, Navarro D, Zhang B, Doman T. Improving hospital mortality prediction with medical named entities and multimodal learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:1811.12276. 2018 Nov 29.

- Bhatia P, Celikkaya B, Khalilia M. End-to-end Joint Entity Extraction and Negation Detection for Clinical Text. arXiv preprint arXiv:1812.05270. 2018 Dec 13.

- Singh G, Bhatia P. Relation Extraction using Explicit Context Conditioning. arXiv preprint arXiv:1902.09271. 2019 Feb 25.

- Bhatia P, Arumae K, Celikkaya B. Dynamic Transfer Learning for Named Entity Recognition. arXiv preprint arXiv:1812.05288. 2018 Dec 13.

- Koda-Kimble MA. Koda-Kimble and Young's applied therapeutics: the clinical use of drugs. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2012 Feb 1.

- Tariq RA, Scherbak Y. Medication Errors. [Updated 2019 Apr 28]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519065/

- Uzuner Ö, Solti I, Cadag E. Extracting medication information from clinical text. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2010 Sep 1;17(5):514-8.

- Patrick J, Li M. High accuracy information extraction of medication information from clinical notes: 2009 i2b2 medication extraction challenge. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2010 Sep 1;17(5):524-7.

- Doan S, Bastarache L, Klimkowski S, Denny JC, Xu H. Integrating existing natural language processing tools for medication extraction from discharge summaries. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2010 Sep 1;17(5):528-31.

- Tao C, Filannino M, Uzuner Ö. Prescription extraction using CRFs and word embeddings. Journal of biomedical informatics. 2017 Aug 1;72:60-6